As you know from reading our earlier blog post in January, Super Bowl XLVII and the Superstars of Ancient Rome had a lot in common with today’s American football stars. There are so many intriguing parallels that we thought the topic deserved another look. So, enjoy part two of this series exploring the connections between the Roman gladiators and the sports celebrities of today.

As you know from reading our earlier blog post in January, Super Bowl XLVII and the Superstars of Ancient Rome had a lot in common with today’s American football stars. There are so many intriguing parallels that we thought the topic deserved another look. So, enjoy part two of this series exploring the connections between the Roman gladiators and the sports celebrities of today.

Much like today’s modern sporting heroes, gladiators had a lot of sex appeal. Just as women today frequent events to see their favourite crush, ancient women would attend gladiatorial games thrilled to see their favourite fighter. And while modern women sometimes have the ability to act on their desires by approaching their sporting crushes at social gatherings or contacting them on Facebook, Roman women did not have the same access. Instead, for the more advantaged woman, she paid to have her desires fulfilled by her favourite gladiator in his cell.

Today’s sporting heroes have lots of merchandise with their names and faces celebrated on everything from t-shirts to cereal boxes. Gladiators also had items that commemorated them and their valiant battles. Two examples are the Colchester Vase and the Gladiator mosaic at the Galleria Borghese.

The Colchester Vase depicts different classes of gladiator fighting each other and also gives the names of each gladiator above him, such as Valentinus and Secundus. From the image below, one can see a secutor facing off against a retiarius; the secutor class of gladiator was cultivated to fight the retiarius class[1]. They were equipped with a tall rectangular shield, a helmet similar to that of the murmillo, greaves and a gladius. To protect the wearer from the deadly net and trident of the retiarius, the secutor’s helmet covered the whole face with two small holes for the eyes and was rounded[2]. While on the other hand, the retiarius was very lightly armoured with only an arm guard, called a manica, in addition to his net and trident. As well as these two individuals, the Colchester Vase depicts a bestiarius. A bestiarius was a beast fighter and in this particular case he is depicted fighting a bear with hunting dogs and a companion.

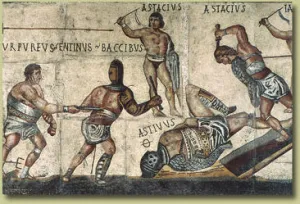

The Gladiator mosaic at the Galleria Borghese also depicts gladiators fighting and has their names written above the figures, such as Baccibus and Astacius. Here again one can discern particular classes of gladiators, such as the secutor and retiarius. An interesting note on this mosaic is the Greek letter Ɵ, for θάνατος meaning “dead”, beside one of the gladiators, who obviously was slain in the fight. This mosaic is a pictorial recreation of a fight that actually occurred and identifies the dead gladiators as well as the victorious ones. Just as modern famous sporting events are memorialized, we can see that famous gladiatorial contests were treated in the same way.

Another interesting similarity between the gladiatorial games and today’s sporting events is the attire of the players. Just as the gladiators wore armour to protect their bodies, many sports today require the players to wear protective gear. One example is American football. While the armour of the gladiator was meant to stop sword and spear thrusts, the armour of the American footballer is there to lessen the impact of the opposition’s tackle.

Unfortunately, armour and padding is not enough to prevent many injuries, and like today’s players, gladiators were a significant investment and were cared for especially well. Similar to modern athletes, gladiators had a highly regulated diet; this consisted of dried fruit, barley, oatmeal, boiled beans and ash, which the Romans believed help fortify the body[3]. After training and fights, the gladiators would be given massages and had access to high class medical care to make sure their master’s investment was properly looked after and fighting fit for the next bout.

Today, when the game or match gets especially out of hand, we have referees who step in and make sure the rules are obeyed. Gladiatorial games also employed referees to help officiate the match. There was the senior referee, called the summa rudis, and an assistant to help him. They had long staffs, called rudes, by which they could separate opponents or caution them. Just like modern day referees, they could pause or stop the match whenever they deemed it necessary[4]. A mosaic from the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid depicts a referee officiating a gladiatorial contest. He is clearly identifiable in a white tunic holding his staff and gesturing to the gladiators.

As in modern times, where one can see the likes of David Beckham spending an evening with Prince Harry in one of the elite London clubs, gladiators were also known to attend banquets and events at the Emperor’s request, an invitation not to be turned down when proffered by such emperors as Domitian and Commodus. Also, just as Princes William and Harry are known to play in charity polo matches, emperors such as Caligula, Titus and Commodus were known to have frequented the arena themselves and take on the persona of a gladiator. Commodus was said to have killed one hundred lions in a day, when he styled himself as a bestiarius [5].

If you love sports today you probably support a specific team, such as the Giants or the Seahawks. The Romans were no different. They supported certain classes of gladiators and each group had its own name: the Romans that supported the secutor class of gladiator (equipped with a large rectangular shield) were called secutarii, while the thraex and murmillo classes’ supporters were called parmularii because those gladiators were equipped with small shields[6]. The same can be said for local rivalries. Just as today when certain groups of football fans (or thugs, as most people would call them) clash before and after the match, the same would occur sporadically after gladiatorial contests. One such occasion occurred at Pompeii during the reign of Nero in 59 AD; insults that were traded by Pompeian and Nucerian fans sparked a riot during a set of gladiatorial games, which caused Nero to ban games in Pompeii for ten years. This incident is depicted on a fresco in the National Museum of Archaeology in Naples, taken from a domus in Pompeii[7].

We may think that our flashy celebrities and loud, exciting sporting events are modern-day creations, but it’s easy to see that the Romans were getting rowdy and turning players/fighters into heroes long before our modern obsession with sporting games. It’s quite obvious that fans’ adoration—and adrenaline highs–trump the boundaries of time and culture.

-Author: Russell Fleming